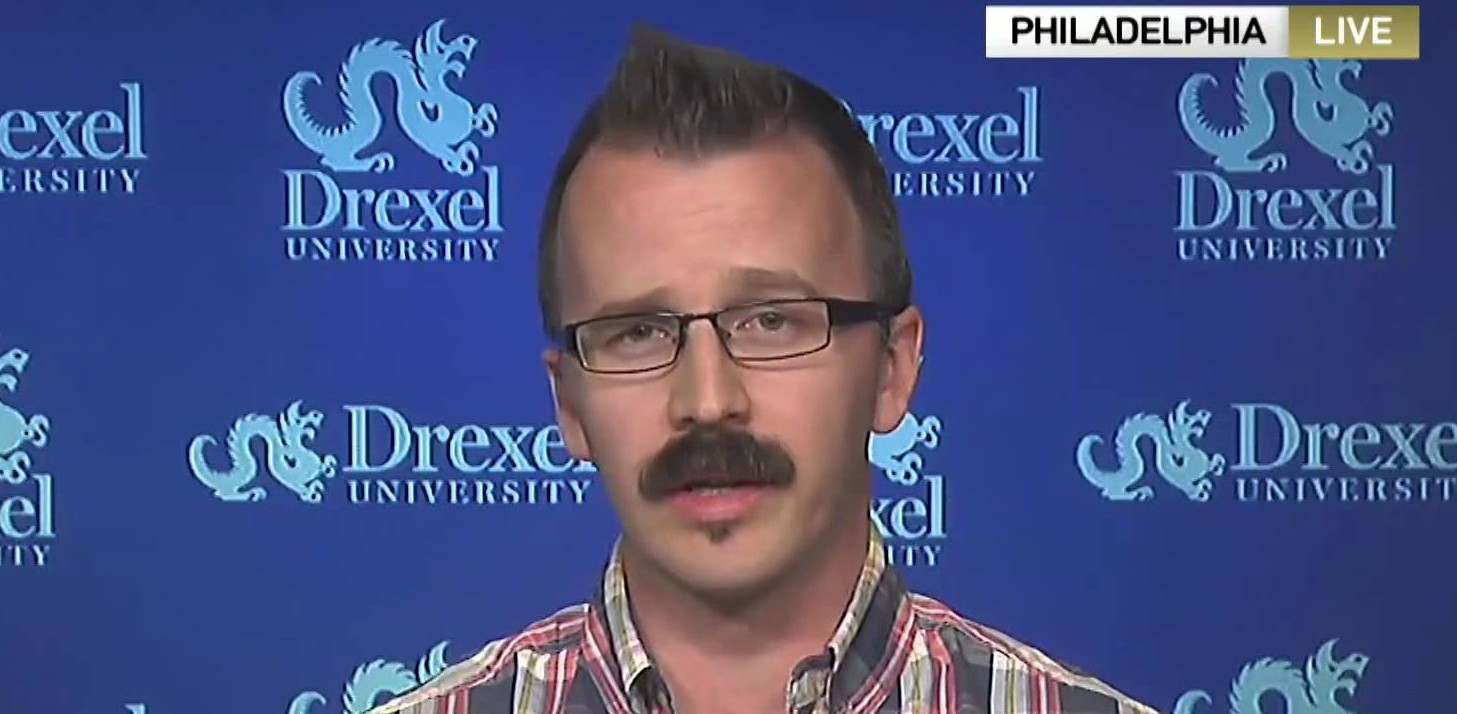

George Ciccariello-Maher is an associate professor of political science at Drexel University who drew national attention earlier this year following a tweet satirizing the White Nationalist theory of “White Genocide.” Professor Ciccariello-Maher sat down with The Triangle to discuss a wide variety of issues ranging from white nationalists and the right-wing media to police brutality, academic freedom, provocative free speech, his classroom philosophy, and his upcoming class, Race and Politics. The class, coded PSCI T180 and scheduled for next fall, will meet on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2 to 3:50 p.m. This interview has been edited for clarity.

The Triangle: I’m interested in your process for tweeting. Are they carefully crafted to produce a desired effect, or are they off-the-cuff?

George Ciccariello-Maher: When I’m tweeting — just like when I’m writing, doing public interviews or speaking with newspapers — I’m trying to intervene in pressing public debates, and after the election of Trump, one of the pressing debates was about this sort of bizarre coalition that had brought Trump to power which consisted of many groups but also included far-right, white nationalist, Nazi and fascist groups. Some of them, they call themselves the “Alt-Right” — the Richard Spencers and the Milo Yiannopouloses of the world. Some of the debates that were emerging around that time, in particular online, had to do with what this meant, what these organizations were representing and what they were pushing for.

When you look at some of the keywords of these far-right, white supremacist groups, one is this phrase “White Genocide.” It’s a reference to a completely made up idea that white people are not only victims but somehow actively being genocided. It refers to everything from politics of diversity to, in particular, intermarriage, in other words the dilution of the purity of the white race, which, again, is an absurd idea. And so, this hashtag popped up in late December, it popped up around some of these white supremacists being opposed to imagery of a black man proposing to a white woman in an ad, and it pops up around different movies if people think that it wasn’t cast right or if it’s showing too many black characters.

So, this first tweet was an intervention into that context. On the one hand, it was a sort of crafted intervention, and on the other hand it — like many tweets — was written off-the-cuff and quickly to make a sharp point. What’s interesting about Twitter is, of course, that it rewards sharp provocation. That’s precisely what 140 characters is for often. And so often these things start debates, start discussions and contribute to broad discussions. In this case, if we’re talking about this concept of “White Genocide,” we had a discussion involving tens of thousands of tweets in early January in which people were having a broad and interesting discussion. Mainstream figures and newspapers like Teen Vogue and others were intervening on this subject and had an opportunity to educate a mainstream readership on these questions.

TT: I want to talk about one tweet in particular, the tweet that read “Some guy gave up his first class seat for a uniformed soldier. People are thanking him. I’m trying not to vomit or yell about Mosul.” Of all the tweets, it seems to most clearly demonstrate that while some of your tweets are inflammatory on the surface, under the surface they’re often trying to address more serious issues. In this case, and correct me if I get this wrong, I’m talking about blind support of the military establishment, especially following a coalition air strike that killed hundreds of civilians in Mosul. Would you agree with that interpretation, and could you explain how you think we should interpret the tweets?

GCM: This is an anti-war tweet, and what’s striking to me is that it was controversial at all, because it’s a very straightforward anti-war, anti-militaristic message. As you said, it was about the precise timing of this bombing that had just occurred, that slaughtered a bunch of civilians, but it was also about this general militarism in our culture.

This was not a tweet actually about a soldier at all; this was not a soldier that I saw. What I did see was a wealthy businessperson giving up a seat, being celebrated for it and being patted on the back for doing something absolutely symbolic in a context in which not only is it the case that, of course, the dead civilians in Mosul were not being shown much respect, but also that those who either volunteer or are conscripted into the military — through economic duress and to get an education for example — don’t get the substantive respect that they need or that they deserve in terms of services, economic stability when they return, psychological services and medical care.

And so, it was a tweet about a militaristic culture that on the one hand celebrates the military, but on the other hand celebrates it in a symbolic way and sends people off to die for who knows what. I think if Donald Trump decides to invade North Korea tomorrow many people would recognize that these missions that people are sent off to die in are not always moral and are not always ethical. That’s something that I think people, in general, in this country need to reflect on more.

TT: When you’re making these are you expecting quite an explosive reaction? Because on the surface, if you read it literally, it definitely seems like it’s talking about one soldier, but you know, that interpretation was taken by some people and not taken by others. Are you expecting such a huge response?

GCM: I think I’ve sent something like 30,000 tweets, and the idea that people expect that a single tweet in particular will set off some kind of media frenzy is really not a reality. Because people are tweeting constantly and people are engaged in conversation, often they’re speaking to other people about a specific context, and then the media will jump in and seize upon it.

The bigger question we need to understand is the actual machinery behind what’s going on right now. We’re living in a moment in which organized and coordinated groups are attacking professors. And I was sort of, maybe, on the early end of this in this year. There are cases in the past, many cases. But we’ve since had more than a dozen cases of groups like Campus Reform, Turning Point USA, The Campus Fix and all these websites — Breitbart — and then up into Fox News targeting professors and looking for anything.

So, we may be talking about my tweets for example, but my good friend and comrade Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor at Princeton was attacked for a graduation speech and was on Fox News four days in a row, leading to death threats against her and her family. There are many cases like this; Tommy Curry at Texas A&M was targeted for a podcast that was four years old, Johnny Eric Williams at Trinity College in Connecticut was targeted for reposting someone else’s words just recently, and he was suspended by his university despite the fact that, of course, he had done nothing whatsoever.

The threats and the discipline are a response to this organized attack that emerges, this kind of online mob that is whipped up. You can never predict, I think, quite when that mob will emerge, and like I’ve said, there’s been dozens of cases since mine, and it’s becoming a really worrying and generalized phenomenon, the way that — professors in particular — but people across the side are being attacked by these organizations.

TT: There are two tweets from 2015 in which you said “#BringBackFields, then do him like #OldYeller” and “Off the Pigs,” which was a slogan of the Black Panthers. Many interpreted these tweets, especially the first one, as advocating for violence against police officers. Do you see this as advocating violence?

GCM: Again, we live in a world, in a country and in a moment in which violence by the police is what we need to be concerned about. Ben Fields tackled a middle schooler brutally. There are thousands of other cases that we could point to of people being really brutalized by the police, police that are really running rampant in our society today, that are seeking unchecked power, that don’t want any kind of oversight of their actions and certainly want no responsibility. When I see those things I get angry; when I see those things it enrages me because we live in a society that claims to be a society of equals, but we know that it isn’t, and that in particular poor people and poor black and brown people are the subject of police violence and constantly on the receiving end of it. That’s really what I’m concerned about.

Of course these are not tweets that call for any kind of violence. If you look at them they don’t, they don’t in any way. They, in one sort of half-satirically and one in a straightforward reference to the Black Panther Party, talk about transforming the society that we live in.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, the MacArthur Genius Prize winner and also one of the most eloquent spokespeople of our moment, speaks in his book “Between the World and Me” about the police as pigs but also about what he calls the pig majority, and in other words those millions of people that allow this to happen, that support it, that uphold it. In a sense, this is similar to the militarism question, right, the blind support for these power structures in our society, and its really that blind support that I think needs to be questioned, that needs to be interrogated and resisted. We need to dismantle that kind of power structure and replace it with something better.

TT: It seems like there is, and I don’t know if this is deliberate, but an inflammatory approach to the specific wording. It reminds me of, over in the conservative realm, someone like Milo Yiannopoulos, who’’s obviously inflammatory in the way that he delivers his message. Putting aside differences in ideology and content, do you think that that approach is valid? Can it produce meaningful discussion? Can it change minds? And is that your goal?

GCM: I mean the first thing to say is that you can’t set aside substantive differences. Milo Yiannopoulos is a fascist, white supremacist. But I think I take your point when it comes to question of being politically provocative, what it does and the way that it functions. This is something that I actually research, study and have observed, for example in Venezuela, but also in political movements in the United States.

Again, to return to the Black Panther Party, this was an organization founded on provocation. What they did was attempt to build self-defense structures in their communities against police violence. But they did so by showing up armed and making public scenes. They went to the California State House — armed — as a provocative sort of political intervention, and what happens when you provoke, often, is that you spark a reaction, and you spark a necessary discussion.

We would not be living in the world that we live in at this moment if it were not for this broad trend that we call Black Lives Matter. Black Lives Matter is not simply about asking for equality and getting it, that’s never been how things happen. It’s about organizing, but it’s also about explosive moments like rebellions in Ferguson and Baltimore, which provocatively produced the need to debate and discuss these things publicly and shifted the public discourse.

In and around the election, the Democrats sort of proved their uselessness, because they don’t understand the role for direct action and for more provocative tactics; they think that everything needs to function within certain political channels. And yet, when people turned out en masse to go resist the Muslim ban in the airports, this was something off the script; something that was much more radical and provoked an effect. What we need to understand is the ways in which this is how politics happens; this how debates happen.

And so, people often try to say that “oh, that tactic is too provocative,” meaning that it’s counterproductive. You can look at some of my tweets, and the reaction, of course, has not all been good, but they’ve been productive debates. Like I said, “White Genocide” is one of the top trends on Twitter and is making it into mainstream newspapers. You can talk about when an anti-fascist punched Richard Spencer in the face, and again people said, “this is counterproductive,” and yet it was very productive because suddenly in the New York Times people were talking about the need to resist Nazis, what it takes to resist Nazis, and whether or not it’s okay to just accept Nazis in our society, or for example [at Drexel] whether it’s okay to accept Nazi flyers being posted up across campus which, of course, it’s not.

I think these kinds of debates are necessary, and I think that the idea that we can avoid provocation misunderstands not only politics, but also the moment that we’re living in. I mean look at the president, someone who does nothing but provoke on Twitter. And if we can’t at least grasp how that has helped him come to power, how that has helped him to generate support in the grassroots, then we can’t understand what’s going on.

TT: In your interview with Tucker Carlson, he asked a legitimate question about the “first-class seat” tweet to which we didn’t really receive a clear answer. He asked “You protected [the tweet], you prevented the public from seeing that right after you tweeted [it]. If you’re proud of what you think, and you can defend what you think, why did you do that?” Can you respond to that question?

GCM: People often protect their tweets on Twitter often because they’re subject to threats of violence against themselves and against their family, and that was what was happening to me. I stand by basically everything I’ve ever said, and yet, that doesn’t mean that I’m not going to try to protect my family, you know, when I need to.

I think the people that say things like this — Tucker is saying it in bad faith, of course, because he understands the way that online mobs work. He understands the fact that when he tweets something or when he says something, he’s essentially calling people out to engage in this kind of threatening action. And he would never of course admit that, nor would he ever take any responsibility for it, and neither would somebody like [Milo Yiannopoulos] — who made his career off of inciting violence and threats against people.

This is what happens, and this is what happened again to my friend professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, who had to cancel a part of her speaking tour because her family was being threatened. That’s not because she’s not proud of what she said, but it’s because the way that these mobs function is an incredibly threatening concrete reality, and we need to understand that this is not about speech, necessarily. It’s about reality; it’s about the actual violence that has been unleashed around the candidacy and election of Trump and the people involved in his coalition. This is actual violence that includes more than 1,000 hate attacks, 40 percent of which mentioned Trump by name. You could listen to my voicemails right now if you want, and you’ll hear the kind of racist, anti-Semitic, misogynistic threats that are on there. You could read some of this pile of mail sitting on my desk that includes incredibly violent and hateful rhetoric.

And so, that’s why people take care of themselves and protect themselves, because these are very dangerous times, and I think if anything is becoming clear it’s that, it’s that we live in times in which these political debates cannot be avoided. But these are not tranquil times in which we’re going to have a calm discussion because first of all, the kind of people that are threatening you are not the kind of people that want to have a discussion with you, and second of all, because you can’t discuss whether Nazism is correct and acceptable. You can’t discuss in debate whether or not certain people are biologically inferior and should be eliminated. You have to reject those ideas, you have to out-organize them and you have to build political movements that can resist them.

TT: During that interview, on various talk shows and in articles following both the “White Genocide” and the “first class-seat” tweets, commentators took your use of the phrase “White Genocide” literally, meaning you were calling for the extermination of white people solely because they are white. The irony in this reading is that the idea of “White Genocide” doesn’t even refer to deliberate killing at all, but rather racial mixing and the dilution of white purity. I was wondering you had any insight into why this literal reading persisted for so long?

GCM: It was entirely cynical, at least for the people that began the controversy. The people that started that controversy were from Breitbart. These are people that know that “White Genocide” is not about killing people, and yet they fed this into the Fox News mainstream with that kind of bad-faith, cynical reading as a way to stoke controversy. And then, once this hits the mainstream, this funny thing happens where you had articles critical of the media coverage. The Philadelphia Citizen wrote an article critical of the media coverage because all you had to do was Google the phrase, right? At the very least I expect my students to Google things, and that’s not even enough, and yet when you have not only students but alumni and people associated with [Drexel University] and media figures and public figures and the general public not even looking up what this might mean, then you know something has gone terribly wrong in our culture.

But there’s a reason why people didn’t bother to, and it’s because over the last 40 years that firstly this is a colorblind society; that we do live in a situation of equality, which is false, and secondly that as a result of that, anyone that’s saying anything about race or talking about race is asking for special privileges and that those special privileges come at the expenses of white people; that white people are victims, again, totally, demonstrably false. And yet, this is a mainstream view. You don’t have to believe that whites are being genocided to believe that whites are on the losing end of affirmative action and all of these other policies, and so this has been a breeding ground for white supremacist ideas because they’ve been able to disguise the ideas of white supremacy behind the ideas of white victimization. So, instead of saying, “we are the master race,” white supremacists put up flyers [at Drexel] saying, “aren’t you tired about everything being against you and being anti-white.” But if you follow the link at the bottom of these flyers that were posted at Drexel it leads to a website and a podcast called the Daily Shoah, Shoah meaning the Jewish Genocide — the Jewish Holocaust. And so, it’s clearly a smokescreen for infiltrating right-wing sentiments and racist sentiments into mainstream society.

TT: Have you ever had any productive discussion with a White Nationalist thinker about the idea of “White Genocide”, who read it not literally like the media read it, but thought about the actual theory?

GCM: I don’t talk to White Nationalists. I think it’s important, you know. People are like, “you should debate Richard Spencer.” I will not debate Richard Spencer. Richard Spencer believes in what he calls slow ethnic cleansing or peaceful ethnic cleansing. You cannot debate with fundamentally irrational ideas. There’s no point because they don’t exist because of rationality.

People are not Nazis because they’ve studied the facts and come to the right conclusions about it, they’re Nazis because they want to have a faith, and you can’t break that faith except by out-organizing them and through making their movements impossible in the streets. You won’t win them over by debating them.

TT: Drexel supported you following the tweets, but later on it opened an investigation into your conduct. InsideHigherEd reported that Drexel had opened an investigation into your tweets, and it cited a letter from Provost Brian Blake saying that the university had lost potential students and donors and been concerned that they couldn’t help admitted students due to the high volume of venomous calls their call centers received. Do you feel any responsibility for both the tangible and intangible negative consequences this has had on Drexel?

GCM: I feel zero responsibility for the fact that white racists started an attack on me, on my family and also on the university because I’m not one of those white racists, because I did not tell them to react in the way that they did and because there’s no reason for them to have reacted the way that they did. They’re reacting that way because they see this as a war against academia and leftists — in particular — in academia. And if we don’t understand that then we miss the point. If you judge things purely by the reaction they provoke then you’re into extremely dangerous territory.

I mentioned some of the dozens of cases that have happened since, in which people have been, of course, attacked and threatened. It’s absolutely clear that what these cases share is not that they’ve done something to provoke threats, but that the threats are there because there are groups that are dedicated and devoted to threatening universities in this kind of way. Johnny Eric Williams was suspended from Trinity College just a couple of weeks ago. Again, he posted something that was not even his own words or thoughts, and yet he was partly suspended because the university was shut down because of threats, it was shut down entirely because of the threats that were being received. In no way is he responsible for those threats.

We all engage in public debates, and sometimes we engage in sharp and important public debates in the knowledge that these things may be controversial. I certainly am engaged in debates that, in this moment, are very controversial, but Drexel University is the kind of university that encourages sharp debates, that encourages faculty to be engaged. It’s not simply about writing academic articles; it’s about engaging in mainstream questions and translating that knowledge into the public sphere. And when you do that in a time of heightened tension, these kinds of things are going to happen. That doesn’t mean that it’s a good thing, but it means that we have to think a lot harder about how we deal with them.

You can’t go around disciplining faculty because of the fact that they themselves have become threatened and been threatened by utterly reactionary and irrational forces that are becoming very powerful in this society. If you do that, there’s no such thing as academic freedom, and if you discipline faculty based on what donors think — in other words, important people with money — then you’ve got no vestige of academic freedom left.

TT: One of the big reactions to your tweets was along the lines of “is this who’s teaching our kids?” So they’ve basically conflated the content of your tweets with your ability to teach in the classroom. Can you give me some insight into your philosophy on in-class debate and discussion. What role do you take? What are they normally like?

GCM: I mean the first thing to say is that, and I say this on the first day of class, “if you’re not uncomfortable, then you’re not doing this right.” We unfortunately have developed the idea that feeling uncomfortable means that we’re being attacked or that we’re somehow being treated badly when we should feel uncomfortable.

People come to college to learn facts, obviously, but also to engage with ideas, to sift through the ideas that they’ve been taught by their parents and by their parent’s parents and by society as a whole, and to think about whether those are ideas worth keeping or whether they should be discarded and replaced with something else, and that process is uncomfortable. If you’re a young white student who’s never realized maybe that you live a relatively privileged life or that others don’t live in the same situation as you or enjoy the same privileges that you do, that can be a discomforting situation. And yet, it’s a very productive situation, and that’s what students, I think, are supposed to pass through is the discomfort that comes with having knowledge challenged.

In the classroom — you can ask any of my former students or you can look at my evaluations — you see that I have great evaluations because students feel like they can say whatever they want as long as they’re backing it up and making an argument for it. They can come into class and question me, and they do question me, and some of my best students are conservative students who have a certain kind of understanding of the world that I largely agree with — about how the world functions, and so we engage in pretty productive discussions and debates about that. You won’t find students who’ve taken my class and feel discriminated against in any way.

TT: Often in the learning process we get things wrong. It’s working through ideas, realizing what makes them wrong and then reworking them that helps to build understanding. Considering the fact that your classes often deal with sensitive topics such as race and political revolutions, what do you think about a student who goes through the material, interprets it and then presents an understanding that some may consider offensive. Are these ideas a valid part of the academic process?

GCM: I mean it certainly would be. It’s difficult, because I think that if we’re talking about things that are offensive often we’re talking about things that are racist, sexist, homophobic sentiments. And I have yet to have a student really stand up and defend those ideas with argumentation.

It’s not just that all ideas are potentially true, it’s that some are true and some are not. Is there a biological difference between black people and white people? No, there is not. And so, it’s hard to try to stand up and make an argument that there is, but I think people struggling with those questions and engaging with those is an important part of the process.

I don’t think what we’re trying to do is shelter students, and so it’s not that any little thing that can be interpreted as offensive should be off limits, but it’s that students should enter the classroom with a level of respect for each other and be willing to engage in those kinds of debates about ideas and about facts.

TT: Can you tell me a bit about the class you’re teaching in the fall?

GCM: So in the fall I’ll be teaching a course called Race and Politics, and it’s open to all students. Hopefully, it’ll be a large class where people can come in, listen to these ideas about the history and the functioning of race, in particular in the United States, and then we can deal with questions like so-called “White Genocide.” We can deal with questions of continued racial inequality today, and what we’ll be struggling over is the fact that race is an imaginary idea, it’s an imaginary concept and yet it’s very real; it has a very real social reality. And that’s something that’s often difficult for people to maintain is this tension between an imaginary idea that really matters, but that’s the world that we live in, and we need to deal with what the political relationship between race and politics is historically — legacies of slavery, mass incarceration today, police brutality and violence, and what it means in our present marked by resistance to that order, the new insistence that black lives do matter.

We’ll be reading texts, for example Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s incredible book “From Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation,” which is really an essential text for anyone attempting to think through what race means in the present today. So, I welcome all students — I don’t care who they are — to come and to be involved in this debate because the point is to have debates, and the point is to have discussions around these questions.