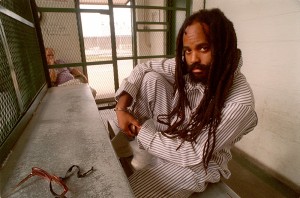

Goddard College in Vermont marches to a different drummer. It held a commencement in early October, and it invited as its guest speaker Mumia Abu-Jamal, America’s foremost political prisoner.

Mumia is currently serving a life sentence in the shooting death of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner in 1981. Until his sentence was commuted in 2011, he had spent nearly three decades on Pennsylvania’s death row. His address was delivered via radio hook-up.

Mumia’s trial was the farce of the century — not counting I suppose all those largely anonymous trials below the Mason-Dixon line where white defendants were routinely acquitted of killing black victims by all-white juries between sips of soda pop before the phrase “civil liberties” entered the vocabulary of the South.

He was beaten silly upon arrest, of course, even though he’d been shot by Faulkner. The gun he was (legally) carrying wasn’t given a routine test for ballistics. A local cop falsely alleged that Mumia had loudly boasted of shooting Faulkner on his way to the hospital; the statement wasn’t admitted into testimony but everyone in Philadelphia had already heard it.

Evidence and witnesses were suppressed. Perjured testimony was coerced from local prostitutes on threat of prosecution; this was later recanted. The jury was vetted on racial grounds, a then-common procedure outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1986 but, although made retroactive, never applied in Mumia’s case because the practice was not objected to in the original trial.

Judge Albert Sabo, a notorious hanging judge who had Mumia bound and gagged in court, was allegedly overheard to remark that he was going to help the prosecution “fry the n—er.” You couldn’t make this stuff up. It was too grotesque to be anything but real. It wasn’t happening in a Mississippi hamlet, though, it was in the City of Brotherly Love.

Mumia has since become an international celebrity; there’s even a street named for him in a suburb of Paris. A professional journalist, he’s written several books in prison and was close to getting a National Public Radio show. The Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police hasn’t forgotten him, either. It has not only lobbied, protested and demonstrated against every attempt by Mumia to obtain a rehearing of his case, but it has exhibited its wrath — and its clout — against anyone even remotely associated with his cause.

Last March, for example, it succeeded singlehandedly in scuttling Barack Obama’s nomination of a highly respected attorney, Debo Adegbile, to head the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department. Adegbile’s offense? He had once, 30 years ago, signed off on an National Association for the Advancement of Colored People affidavit on Mumia’s behalf.

The nomination was defeated in a Democratic-controlled Senate. Not a single one of the 52 senators who voted against Adegbile had a word to say against his record, nor would any deny that he was acting strictly within the bounds of propriety in Mumia’s case — indeed, within the bounds of any accused person’s right to legal defense and assistance under the law.

We knew that the banks own Congress, because Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois told us so. But it appears that the Fraternal Order of Police is a not-so-silent partner too.

Needless to say, Goddard’s invitation to Mumia outraged the FOP and its political lackeys. That great public servant, Republican State Rep. Mike Vereb, immediately introduced a bill in the Pennsylvania General Assembly to give crime victims and their families the right to bring a civil suit against any offender — even after release from prison — to halt conduct that they claimed would be detrimental to their peace of mind.

Governor Tom Corbett quickly announced his support for the bill, giving voters of the Commonwealth yet another reason to turn him out of office next month.

Behind bars, Mumia has become one of the most eloquent defenders and practitioners of free speech of his generation. Reason aplenty, to be sure, to shut him up. And reason for those of us who value what is left of the First Amendment to ensure that he can continue to be heard. Mumia is an astute and perceptive observer of American politics. Above all, however, he is a voice for the voiceless — the more than two million men and women in our prisons.

But, isn’t Mumia a cop-killer? We will never know with certitude who killed Daniel Faulkner, and we will never know with certitude that it was not Mumia Abu-Jamal. Personally, I have become convinced that there was likely a third shooter on the scene of Daniel Faulkner’s death whose presence was deliberately ignored or covered up.

The Philadelphia police had been gunning for Mumia ever since he had been called out by Mayor (and former Police Commissioner) Frank Rizzo, who told him publicly that his breed of journalists would be “held responsible and accountable” for their writings. The idea of the chief executive of the city threatening a private citizen with harm before witnesses tells you all you need to know about Philly justice 30 to 40 years ago. The opportunity to get Mumia, once presented, was not going to be missed.

Mumia Abu-Jamal deserved a fair trial, whatever the merits of the case against him. What he got was an absolute travesty of the law, a textbook case of political persecution against a young journalist who had become a target by associating himself with two highly unpopular groups, the Black Panthers and MOVE.

What he deserves now, apart from justice, is the right to be heard. That right, if denied to him, is also denied to the rest of us. Goddard College had the right idea. It would be even more appropriate, and significant, for a university in Philadelphia to afford Mumia a similar opportunity — Drexel, for example, would be an excellent place.

Robert Zaller is a professor of history at Drexel University. He can be contacted at [email protected].