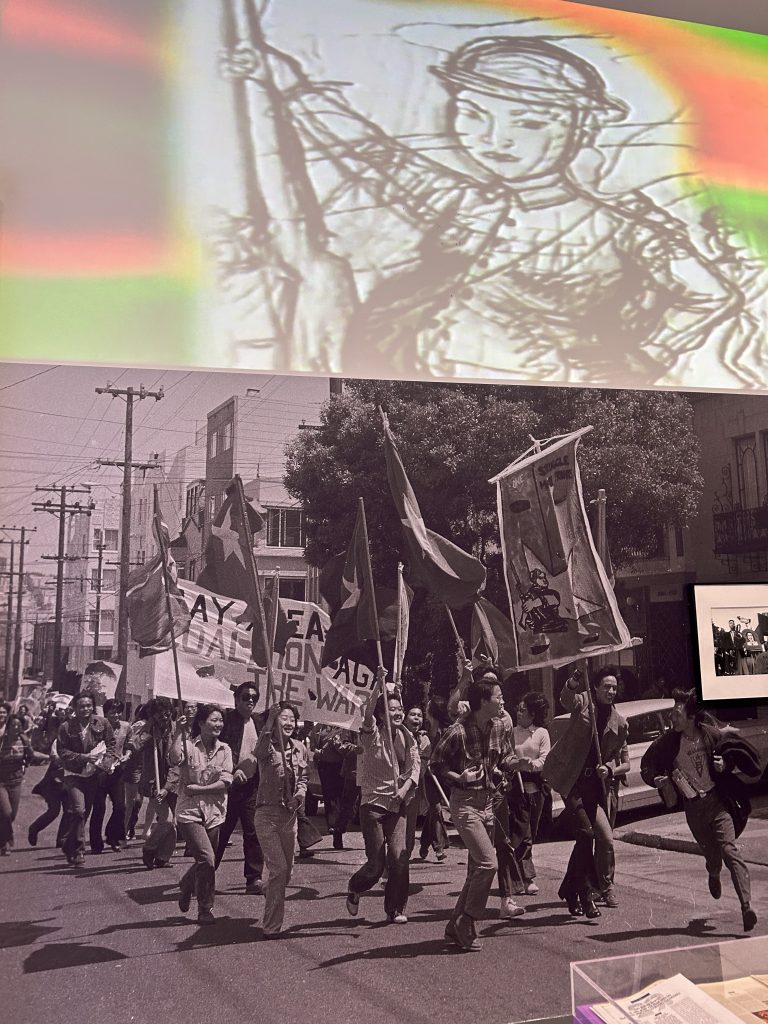

From now until the end of June there is a new exhibition available at Chinatown north’s Asian Arts Initiative. Titled “Crescendo: How Art Makes Movements,” the collection highlights the Asian art and social movement that occurred throughout the ’80s and ’90s. It consists of hundreds of artifacts from the period, such as books, newspapers, paintings, music and much more. It also contains two new art collections, all intended to reflect the message of the original movement.

To put it simply, the movement was one of a kind. As the exhibit’s curator Joyce Chung stated at its opening night, it was the “first Asian-American-led art movement,” and one that was both “interracial and interdisciplinary.” What this means is that the movement was both involved and inspired by other races, particularly Black people.

“Black art and Black power movements inspired Asian Americans,” stated exhibit panelist and artist Salim Washington. “And a lot of this art included Jazz.” The genre served as one of the main mediums for cultural expression throughout the period. Similar to how artists like John Coltrane and Charlie Parker used music to convey their messages decades before, now Asian musicians were taking a shot at it, and there is no doubt that they did it justice.

The exhibit explores three musical projects that were created during the period. One of these was Asian Improv Records/aRts, which was co-founded by another exhibit panelist, Jon Jang. According to the exhibit’s website, the collective “created social, cultural, and political spaces for artists with Asian heritage to explore the complexities of the Asian American experience.” This is similar to the goal of the other two groups featured, the The Afro Asian Music Ensemble and The Far East Side Band, both of which were centered around musical solidarity between Black and Asian cultures.

However, it is important to note that this sort of collaboration is a far cry from the appropriation of Jazz that has been going on over the last few decades. The artists involved in the movement were not stealing the styles and techniques of their Black counterparts, rather, they were genuinely inspired by them and felt the art forms that they pioneered were great methods of capturing and making something truly beautiful out of a comparable struggle. As Washington put best: “Jazz has been colonized. This is not that.” Respect is a two way street, and since the Asian musicians respected the art form and the spaces associated with it, the respect has seemingly been more than returned.

A main reason for this is that the two cultures have repeatedly faced and continue to face similar struggles. One glaring example of this is the fact that this whole movement and all the incredible art associated with it has been relatively marginalized, and has not been given nearly the respect and admiration it deserves. One of the panelists, visual artist Theodore Harris, discussed how like the Black Arts Movement of the ’60s and ’70s, this period of Asian cultural renaissance has largely been forgotten about by the general public, if they even knew about it at all. He mentioned Larry Neal, a writer, poet and briefly a Drexel professor who was a big player in the Black Arts Movement, and talked about how a lot of people have no idea who he was and the impact that he had. To Harris, that is why exhibits like these are so important. Whether intentionally or not, movements like these slowly get erased with time. If it were not for someone like Joyce, who made it her mission to preserve the history of this incredible cultural era, then there is a good chance that not a lot of people would remember or even know about it, and it would end up as just another example of a forgotten moment in time.