On Wednesday, Oct. 12, press arrived at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA)’s preview for the anticipated “Matisse in the 1930s” exhibit.

PMA is in collaboration with Paris’ Musée de l’Orangerie and Nice’s Musée Matisse Nice to showcase the first major exhibition dedicated to the pivotal decade and art of world renound artist Henri Matisse (1869–1954).

Outside the Exhibit

Outside the museum stood the PMA Union: the first “wall-to-wall” union at a major art museum in the US. They represent about 190 workers in most departments including curational and conservation workers along with retail and development staff.

Union members believe museum management has continuously engaged in union busting and Unfair Labor Practices. A contract has been circulating for two years yet management has not acted on the issues.

While workers were on strike, management used non-union “scab” workers to perform their work, including installing paintings for “Matisse in the 1930s” and giving misrepresented negotiations to PMA staff, city officials, and the public.

Matt Carrieri, Local 397 Executive Board Member at Large stated, “the biggest news of the season isn’t the Matisse opening; it’s the incredible spirit and solidarity of the PMA workers in the face of management’s abject failures.”

According to National survey data from the Association of Art Museum Directors and PMA’s financial disclosure forms, executive positions are compensated at rates close to 50% more than executive positions at other art museums while unionized staff makes on average about 30% less than the staff doing comparable jobs at other museums.

On Oct. 14, PMA workers and museum management reached a contract agreement, including 14% wage increases through June 2025, cost reduction on health care plans, four weeks of paternity leave, and increasing the minimum wage to $16.75/hour. 19 days later, workers returned to their jobs.

Attendees saw the contrast of the museum’s interior versus exterior. Luncheon tables were accompanied by illustrated scholarly catalogs and waiters serving well-cooked platters as conversations regarding art and the union strike continued.

University of Pennsylvania Sophomore Irma Kiss-Barath was appalled by the “irony of fine dining indoors while outside workers don’t even make a living wage…”

“But Matisse is all about sensory pleasures!” she added sarcastically.

Ironically, both the strike and PMA’s new director and chief executive Sasha Suda began their work the same day. Having had previous experience at the National Gallery of Canada and unionized workforce, observers were disappointed with Suda’s inaction.

During the luncheon, Suda spoke her perspective, stating “We’ll get there in time… The last few years have been an immovable block in history. A turning point. We are looking forward to a new beginning.”

Inside the Exhibit

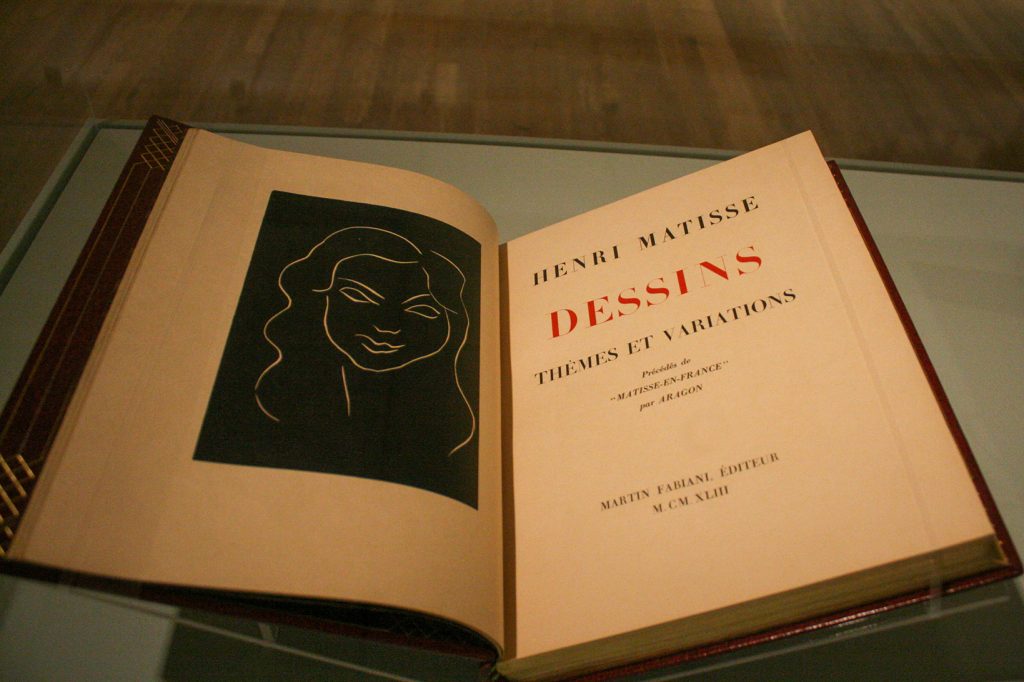

Philadelphia’s “Matisse in the 1930s” includes about 140 works, including renowned and rarely seen paintings and sculptures, drawings and prints, illustrated books and documentary photographs and films.

The partnership’s curational team includes curators of modern art at PMA: Matthew Affron, Muriel and Philip Berman, Cécile Debray (President of the Musée National Picasso-Paris) and Claudine Grammont, director of Musée Matisse Nice.

The collaboration enables PMA to vividly portray Matisse and his Philadelphia story, utilizing the deep connection between each institution.

Matisse’s transformative years were influenced by obtaining his worldly vision through his residence in Nice and his 1930s visit to Philadelphia. This era had never been featured in a standalone exhibition before and PMA offers a rare opportunity to immerse visitors in his creative process, new methods and career outlook.

Affron noted his “decorative environment is crucial… [it’s] something about the space… you need to look twice to see it.”

Matisse was “a man in touch with his times … and in touch with the history behind him” from updating Delacroix and Renoir’s traditions to his Avant Garde transformation.

An attendee adds “It’s not completely out of time. It’s not completely related to Delacroix and Renoir. It’s also the present.”

Following his Philadelphia visit, Matisse drifted from his 1920s naturalistic space concept to a flatter, bolder and larger approach while maintaining the emotion from his original work.

Drawing was typically Matisse’s basic building block. He would use charcoal to understand his motif through tone, shadow and range. Next, he drew unalterable, pure, un-shadowed modulated line in ink.

The relationship between these drawings built his understanding of details for his final piece. Rumor says once Matisse learned the motif, he barely looked at the model.

Many artists get lost in the process versus the final product, yet Matisse used his own methods to combine the two concepts.

For example, he was discontent with his weaved tapestry, so he tested various medians until he was happy with the final product.

In another instance, Matisse painted charcoal on canvas, a technique typically used for sketches or mural paintings. He displayed this artwork on the wall of his study to clarify its completion while wanting people to wonder his median used and degree of completion.

Matisse even had his model fabricate herself a skirt. In this portrait, he separated the line design from color yet still created rhythm and interaction.

Later in his career, Matisse’s primary inspiration became dance. He drew lines as dancers rather than painting figures, showing dance’s hold on his imagination. His inspiration is linked to his U.S. travels and re-emerging his 1930s modernist style.

The final exhibit concluded Matisse’s story with drawings from his remaining days and reflection on his process. He illustrated books with his methods and themes, showcasing his drawings in a linear fashion and teaching the mechanics of his work.

The end of the gallery showcased “Seated Woman with a Vase of Amaryllis” (1942) a painting where all his themes come together in reflection of his career, conveying the well-known feelings to the viewer.

Overall, the museum collaboration between Philadelphia, Paris, and Nice “offer a special, much-anticipated opportunity for a new and unparalleled exhibition about this decade.” Debray adds that “above all, the collaboration marks a friendship” regarding her colleagues and friends, Claudine Grammont and Matthew Affron.