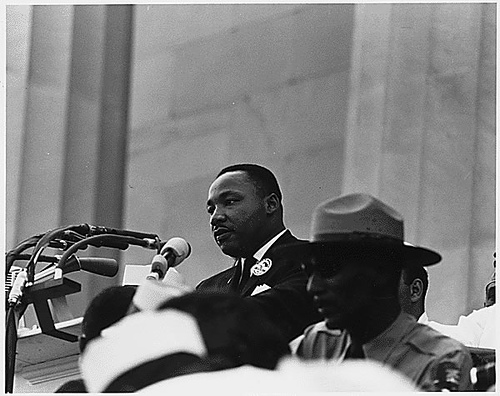

April 4 marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee. King is now a national martyr, his birthday a public holiday and his statue, a towering figure that has always seemed to me a grotesque misrepresentation of a fundamentally humble man, on the Washington Mall. Only hours later, Robert F. Kennedy, himself the brother of an assassinated president and now a presidential candidate himself, broke the news of King’s death before a largely black audience that had gathered to hear him in Indianapolis. Two months later, Kennedy himself would be slain in Los Angeles following his victory in the California Democratic primary.

Those of us who remember the spring of 1968 can still experience the sense of a country coming apart. Newark and Detroit had already burned; Washington would soon follow. Rent by the Vietnam War and racial division, the country appeared to be coming apart. The double shock of the King and Kennedy assassinations seemed to have sealed its fate. There were no leaders left who were not already discredited or bent themselves on further violence.

Nations do not easily disappear. Germany survived Hitler. France, Russia and China survived their own bloody revolutions. They did so with a generous dose of amnesia. America survived as well in the anaesthetized 1970s and the Reaganized 1980s. The great upheaval of the sixties became a hippie carnival and a selling point for commercial products, none of which was for awhile without a ticket advertising it as “revolutionary.” The ruins of the inner cities lay where they were. Detroit cratered, and even Washington was slow to rebuild.

The ruins made their point: they were a new, de facto segregation that trapped those who lived with them, reminding them that poverty was not a condition to be overcome but a punishment and a destiny for those who had rebelled against it.

As for war and empire, they barely missed a beat. Vietnam became not a moral crisis, but a “syndrome” for the governing class to manage, essentially by converting a citizen army into a mercenary one, with shadowy accomplices in the CIA, so-called special forces, and private contractors who carried on the work of seeding the world with military bases and killing in remote places. By the early 1990s, we would be ready to resume our wars; now, in 2018, they have become a permanent enterprise, and so much a part of our climate that we no longer recognize a world without conflict. Call it peacewar.

There was another cost of the assassinations. That of John F. Kennedy in 1963 was blamed on a lone gunman; so were those of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. Conspiracy theories mushroomed in their wake, often tied to suspicions of a “deep state” within the state that had scores to settle or secrets to hide, and ultimately formed the core of government power. The fact that both Jack and Bobby Kennedy had themselves ordered the assassination of foreign leaders gave credence to this idea, and fed a growing sense of alienation from political institutions as such. In the early 1960s, 70 percent of Americans professed confidence that their government could, in general, be trusted to do the right thing. Today, that number is in the low double digits. We have, in effect, abandoned our belief in the institutions of our Republic.

That belief had already been sorely tried by the sixties. Mass marches hadn’t stopped the Vietnam War; urban violence brought only brutal repression. The King and Kennedy assassinations seemed to have sealed the bill: as the journalist Jack Newfield wrote at the time, America had now killed its only hope for leadership, and Martin Luther King Jr. had been wrong about getting to the mountaintop. The stone, said Newfield, had rolled to the bottom of the hill, and things would only get worse.

This prediction was prescient. From the Civil War on, each American generation had produced mass movements for change: Reconstruction, Populism, Progressivism, the New Deal, the New Left. None of them had been more than partially successful, but all of them had affected public policy. Since 1968, no such movement has arisen, and a hardened Right, cynically manipulated by political and corporate elites, has driven the national agenda. The result has been unabatedly rising inequality, waves of debt-fueled economic crisis, and repression by mass incarceration. Intermediate institutions — families, worker unions, an independent media — have been weakened or crushed. Pushback has been virtually nil.

Perhaps the one moment when hope apparently revived was with Barack Obama’s election as president in 2008. That an African-American could have been chosen to lead the country at all seemed to vindicate at least part of King’s dream. It proved, however, only a final disillusionment. Within two years, Obama had lost his Congressional majority; a year later, a brief flicker of resistance, the so-called Occupy movement, vainly protested the wave of personal bankruptcies and home foreclosures that had followed on Obama’s Wall Street-friendly economic policies by squatting in public places. Police batons and water hoses weren’t needed to disperse it. Cold weather did the trick.

The swiftly dashed hopes of the Obama years set the stage for the 2016 elections, in which populist insurgencies on the Left and Right effectively repudiated both major political parties. The Democrats fended off their independent challenger, Bernie Sanders. The Republicans succumbed to theirs, Donald Trump. Trump wasn’t elected because of any qualification for office, but as a brick to smash the system it represented. Since, at bottom, the system is adamant, Trump understands his role to be that of an entertainer, feeding the public a daily diet of scandal and outrage. In this, he has thus far been successful, while tending to his own business fortunes and servicing the elites on whose sufferance he depends. If he is neither stable nor intelligent enough to be a genuine demagogue, he has made the presidency into a vessel of demagoguery for some more focused personality.

That is where the 50 years since Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination have left us. King’s vision of social justice was the greatest we have had since Abraham Lincoln’s, and he has had no successor. I saw Robert Kennedy try, haltingly, to step up to his place on that terrible night of April 4. Tragedy had tempered him, and made of that famously ruthless personality perhaps something that greatness could have entered. We’ll never know. He recited that night the lines of Aeschylus about the pain that falls upon the heart. How many would have understood him in the shock of their grief, or have known who Aeschylus was? But that slight figure, standing alone in an anguished multitude, found the words of a universal compassion.

We have not heard them since.